The philosopher, linguist and novelist Umberto Eco described libraries as a form of repository, or bank, which served to secure the written word and the treasures of the text.

The essential nature of the library, even today, is therefore one of contradiction: where the traditional processes of cataloguing and classification act to hide and ‘lose’ books as much as they reveal and allow access to books.

Such a view seems appropriate in the week that the British Library seems to have ‘mislaid’ 9,000 books.

A recent article in the Guardian highlighted that visitors to the British Library discovered

Renaissance treatises on theology and alchemy, a medieval text on astronomy, first editions of 19th- and 20th-century novels, and a luxury edition of Mein Kampf produced in 1939 to celebrate Hitler’s 50th birthday

were all apparently missing.

And I suspect that this is a situation that almost all libraries, special collections and archives can sympathise with.

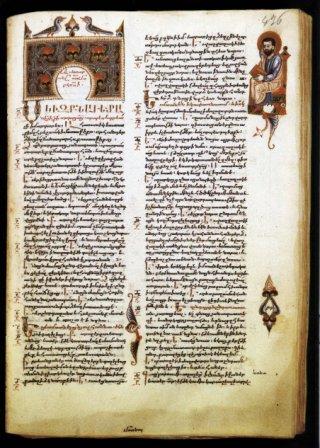

What is interesting about this case is that the digitisation of such precious texts represents an opportunity to not only preserve these texts and the knowledge they contain, but also to open up access for everyone who might be interested in these works.

While there are often financial, infrastructural and ideological barriers to digitising such material, it is hard to imagine a better illustration of why digitisation is such an important part of an institutions practices.