Martin Poulter, Jisc Wikimedia Ambassador, took part in one of the Spotlight on the Digital focus groups looking at what content creators can do to increase the discoverability of their digitised collections.

Here he discusses some ideas on how best to engage with the Wikimedia family.

The Wikimedia family of projects have a unique role to play in guiding both specialist and general audiences to scholarly and educational content, but there are better and worse ways to engage. Here are some tentative principles of discoverability from a Wikimedian perspective.

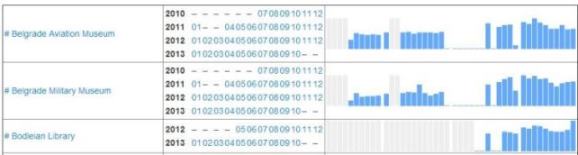

Sharing content outside your own site does not mean losing track of its usage. Each digital media file uploaded to Commons has an auto-generated list of the Wikipedia articles and other project pages where it is embedded (an example- scroll down to “File usage on other wikis”). Daily view statistics for every page on Wikipedia are publicly available through the stats tool. These data are available through APIs where they can be used by other scripts, for example the BaGLAMa tool, which counts monthly hits on images from different source organisations.

We could be using content to promote the projects, not vice versa. For example, I’m aware of and make use of the medical illustrations of Patrick J. Lynch, not because I’ve ever visited his site (if he even has one) but because I found the illustrations in Wikipedia articles about the lungs or the brain. These have led me to Wikimedia Commons where the images are hosted with attribution.

We should pursue our and Wikimedia’s shared goal of bringing knowledge and culture to a mass audience, and avoid the pitfall of thinking of Wikimedia in marketing terms. If you have a project about, say, 16th century poetry, the priority in engaging with Wikipedia should not be to create an article about the project. Not only are the costs greater in terms of suspicion and resistance from the Wikipedia community, but the benefits are comparatively tiny because the target audiences are likely searching for “16th century poetry” and related terms, not the project name.

Transparency is non-optional. Getting content into Wikimedia is not a matter of infiltration: it’s an opportunity to celebrate and draw attention to the content and to the organisation that contributes it. Contributing organisations need always to be transparent about what they are doing, to avoid suspicion and blowback from existing contributors. Fortunately, there are lots of ways to do that, with formal content sharing agreements, badges, user profiles and project pages.

There tools are already being used by Europeana, the British Library and other cultural institutions. Where there is a conflict of interest, there are ways to manage it, including requesting changes. This involves waiting for an unpaid volunteer to respond to the request and so it can be frustrating that things don’t happen immediately, but this goes with the territory with Wikipedia being a community-driven site. The community will look more favourably on parties that are seen to be positive contributors (usually by sharing images) rather than parties who only ask the community for favours.

The key advantage of an open, collaborative environment is that it enables the division of labour. This means that projects can focus on their strengths. A typical digital content project might produce:

– digital objects

– metadata about those objects

– an interface

– design/branding, eg domain name, logo.

But a project can have impact and be valued without doing all four. For instance the British Library’s Picturing Canada project has 2000 public-domain photographs with links back to the BL catalogue records, but does not have its own web site or branding. People will find the content not by going to a dedicated site and using its custom interface, but from search queries in Google or Commons for “porcupine wildfire” or “Wilfrid Laurier”, or from browsing Wikipedia articles where these images are embedded. So that’s a small collection with content and metadata which will get a lot of impact without even having a web site, and without having to worry about domain name registration, software installation, and so on.

Another example of this principle is that a collection might have interesting resources and a great, usable interface, but no metadata, in which case it could get some metadata by crowdsourcing.

Contextualisation is crucial – arguably the whole problem of getting attention on, and reuse of, digital content is the problem of contextualising it usefully and efficiently. There are many layers of context. For an image in a collage, within a worksheet, in a set of course materials, in a learning community, there are several content/context relations. In each case, quality content improves the context, while the context brings people to the content and makes it memorable. A map showing the location of Hastings on the English coast might not be interesting in itself, but in the context of an article about the battle of Hastings it’s something that every schoolchild is at some point has to consult. So Wikipedia is a context in many senses: articles are context for an image or link, but Wikipedia itself is a vital context as an extremely popular web site.

One aspect of context is the kind of link. There are two kinds of external links in Wikipedia articles: citations that support claims made in the article, and links to additional encyclopedic resources (in a section called “External links”). A common observation is that users follow citations much more than “external links”, and that’s not surprising since “external links” are more ephemeral and more likely to be a target for spam.

Part of encouraging contextualisation means rejecting paternalism, or in other words making the bare minimum number of decisions on behalf of the user. One obvious consequence of this is the virtue of free licences which put the fewest restrictions on use by the end user. However, in the context of digital media this also applies to the technical ease of remixing and repurposing. Wikimedia Commons invites people to restore or touch up images (and one of its virtues is that allows the crowd-sourcing of image restoration) but makes both the original and the improved versions available (example) since they are both useful to different audiences.

Another corollary is that any piece of metadata is potentially a navigational tool. Not just “more by this author”, “more from this time period”, “more from this geographical location”, “more pictures depicting this person”, “more with this theme”, and “more with this IP licence” but any other attribute. Every piece of metadata could be a clickable link to more items with the same property (like the categories at the foot of any Wikmedia Commons page), and if we’re not doing that, then why are we sure the users will never want that query?

I was glad that there were many comments at the meeting about opening up the silos. Having multiple incompatible interfaces with different content is a kind of paternalism, because it makes choices for the user. Let’s say a project has an excellent image annotation tool for its collection of medieval manuscripts. I’m keen to use it, but on another project’s collection public domain maps. Probably I can’t. Contrast that experience with Wikimedia, whose ecology is agnostic about subject matter. When a developer makes a tool for classifying images of animals in Commons, the same tool could classify any other sort of image, and so could be used and improved by a completely different community. This does not mean everyone is forced into a particular software or programming language; just that there is a common, open API.

(This post is licenced under CC-BY-SA)

2 replies on “What Wikimedia can do for digitised content”

[…] have focused on discussing of three kinds of opportunity: using Wikipedia in education, promoting content collections such as image archives, and expanding the impact of […]

[…] and gave a presentation about Wikimedia Commons, Wikisource and Wikipedia, following up with a written briefing. The final report mentions Wikimedia under the headings of “Content promotion” and “Foresight […]